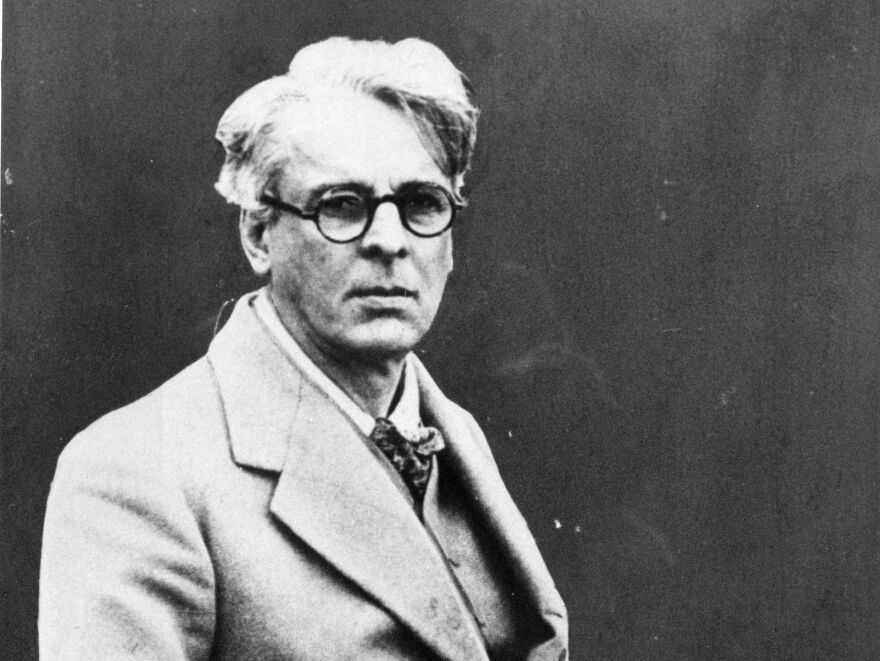

William Butler Yeats wrote "The Second Coming" a hundred years ago, when the world seemed on the verge. Perhaps like now, perhaps like many years.

The losses of the First World War were still overwhelming when millions more began to die in the waves of a flu pandemic, which infected Yeats's wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees, while she was pregnant. She and their child would survive.

Yeats's poem was published in November 1920. And over the century since, perhaps no poem has been more invoked for vexing times, to convey, in Yeats's own incomparable words, that:

"Things fall apart; the center cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, / The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned; / The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity."

I would scarcely call "The Second Coming" a holiday poem. But it makes you feel that that a page of history is about to flip: one epoch is about to give birth to another. And what kind of times will be wrought from a world where, "the worst are full of passionate intensity?" Yeats asks:

"And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?"

Over the past century, Joan Didion, Chinua Achebe, Lou Reed, Stephen King, and scores of other writers and artists have taken phrases from Yeats's poem as lines and titles of their own works.

Yet as Roy Peter Clark, Senior Scholar at the Poynter Institute, notes in an elegant recent post, history must also note that William Butler Yeats became enamored of nationalist authoritarian movements, including fascism. He said admiring things about Mussolini and eugenics. He wrote a few anthems for the Blueshirts, an Irish fascist group. When we read, recite, or fire our minds with Yeats's poem, do we somehow condone the devastating ideas which he came to favor? What works do we choose to keep or discard as we reconsider our history and art?

Ann Patchett, the novelist and memoirist, told us this week that, "If we applied today's morals to dead artists, then history would be fairly scrubbed of art. The question to ask is, 'Does this poem still speak to people?' Yeats passes the test. It continually means something new because that's what great art does - it is reinvented, re-energized, by the person who reads it."

What we make of Yeats's poem a century later is like the history ahead, waiting to be made: it's up to us.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.