Forty years ago, the most serious nuclear accident in U.S. history sparked a backlash against the industry and halted its growth for decades. Today, the remaining working reactor at Three Mile Island, Unit 1, faces new challenges, including cheaper competition in a rapidly shifting energy grid. Unit 1 at the plant, near Harrisburg, Pa., is slated to close later this year.

But mounting concerns about climate change, and the need for zero-carbon power, are also driving a new push to keep Three Mile Island and other nuclear reactors open. It's a turnaround few would have foreseen in the chaotic days after the accident.

Confusion and fear

On March 28, 1979, Three Mile Island's Unit 2 reactor suffered a partial meltdown after a pump stopped sending water to the steam generators that removed heat from the reactor core. The accident was a combination of human error, design deficiencies and equipment failures.

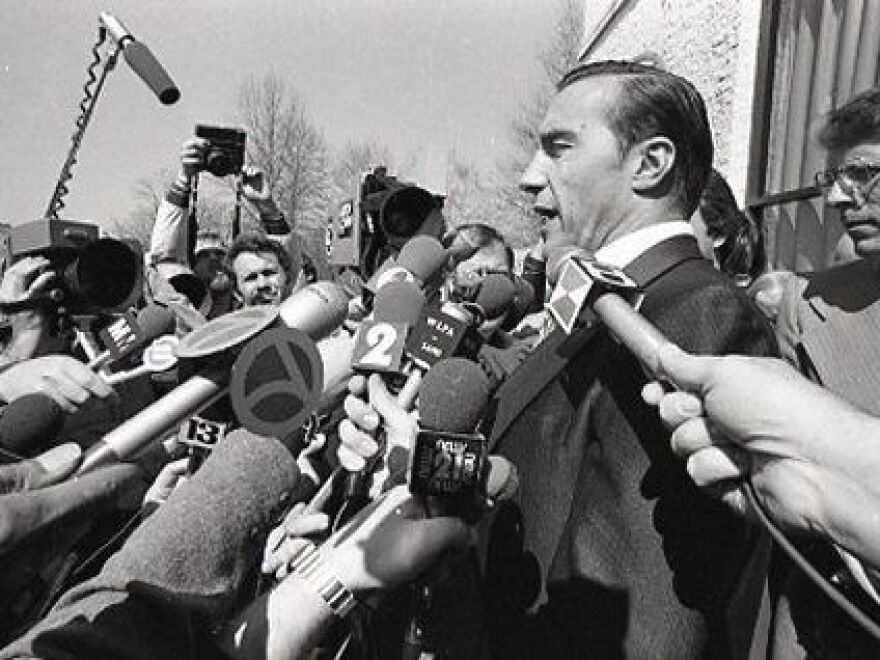

The accident happened around 4 a.m. on a Wednesday, but it took several days before people understood the severity of the problem, as public officials struggled to explain what was happening. By Friday, then-Gov. Dick Thornburgh recommended that pregnant women and young children evacuate.

Many more people chose to leave. By the end of the weekend, an estimated 80,000 people had fled south-central Pennsylvania. Schools and businesses closed. Local banks started running out of cash.

Joyce Corradi was a young mother of four, running a day care out of her home in Middletown, a few miles from the plant. Her most vivid memory is pulling out of her driveway, wondering if her life would ever be the same.

"I took our marriage certificate and I took our children's birth certificates," Corradi says. "I was concerned that, if in the confusion things really got bad, that I could prove those were my children and that we could at least be together."

She would return 10 days later. A small amount of radiation was released, but in the end, it wasn't a disaster. In 1985, Three Mile Island reopened, minus the one damaged reactor. Although some of her friends moved away, Corradi still lives in the same house, but feels the plant always looming in the background.

"It's kind of like living with a giant in your neighborhood," she says. "You know it's there. You know it could cause you problems, but you live in an uneasy compromise."

A new challenge to the nuclear industry

That compromise is being tested, as the nuclear industry faces new challenges, including high operating costs, stagnant demand for electricity and competition from cheaper natural gas and renewable energy.

Chicago-based Exelon, the current owner of Three Mile Island's still-functional Unit 1 reactor, says the plant has been losing money for years. The company plans to close it this fall, 15 years before its operating license expires.

David Fein, Exelon's senior vice president of state governmental and regulatory affairs, says the company is still hoping the state government can step in to keep it open. He argues that losing so much carbon-free electricity would be a major blow to efforts to combat climate change.

"It's something that, if we hope to do anything about it, then we have to preserve all the nation's nuclear power stations," says Fein.

Nuclear power provides about 20 percent of the nation's electricity. Yet across the country, nearly a third of existing nuclear plants are either unprofitable or scheduled to close.

There is only one nuclear plant under construction in the country, in Georgia, but it's years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget. Energy Secretary Rick Perry visited the construction site last week to announce $3.7 billion in federal loan guarantees for the project.

Pennsylvania's five existing nuclear plants account for about 93 percent of the state's carbon-free power. Mark Szybist, a senior attorney with Natural Resources Defense Council, says that without new policies, nuclear plant closures could lead to more greenhouse gas emissions.

"We're at a point where if nuclear retires immediately, we would probably replace it with natural gas generation because we haven't sufficiently planned to replace it with something cleaner," he says.

Climate change and the push for zero-carbon energy

All of this has led to a big lobbying effort to keep nuclear plants online. In recent years, other states — including New York, Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut — have given billions of dollars in subsidies to keep their nuclear plants open. Ohio is considering doing the same.

Christina Simeone, a senior fellow with the University of Pennsylvania's Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, thinks governments should step in.

"Once you close a nuclear plant, that's a permanent result," she says. "We're going to lose a significant amount of zero-carbon power."

In addition to Three Mile Island, FirstEnergy's Beaver Valley plant near Pittsburgh is also slated for an early retirement — in 2021. Republican state Rep. Thomas Mehaffie recently introduced a bill to try to keep the Pennsylvania plants open.

"If we lose one or more of these plants we might as well forget about all the time and money we've invested in wind and solar," says Mehaffie.

But his bill faces major opposition, from groups like the growing natural gas industry, which stands to gain if nuclear plants close, and the AARP, which says the move would hurt ratepayers.

Carbon pricing

A report published last year by Pennsylvania's bipartisan Nuclear Energy Caucus called carbon pricing the best "long-term" solution for the state to address the economic woes of nuclear plants.

The regional grid operator for the Mid-Atlantic and parts of the Midwest, PJM, has also said putting a price on carbon is the best way for state governments to address the climate change concerns that have emerged amid their nuclear debates.

As someone who lived through the Three Mile Island accident, Joyce Corradi would be happier to see the plant close. But because the U.S. still has no real plan to deal with its radioactive nuclear waste, it will still be stored at the plant, sitting in her town indefinitely.

Even today, she avoids driving by the plant's large, gray cooling towers.

"I find that really, 40 years down the road," she says, "I'm still sitting on top of a plant that has all the waste, a plant that cannot sell its electricity, and there's still no real answers."

Copyright 2024 WITF